( Thomas Holme )

William Penn received title to the land from the British King Charles II in 1681 as a proprietary grant in payment of a debt owed Penn’s father.

Penn decided to locate his city at a site that would cause minimum disruption to established residents and to treat the Lenni Lenape as generously as possible by paying them to give up their claims to the land.

Penn then began to plan the city that would embody his so-called Holy Experiment, in which men of all races and creeds would govern themselves in complete religious, political, and intellectual freedom. As a result the city became a haven for Quakers and other religious and political dissenters.

Philadelphia also became the center for many profitable commercial ventures. Eighteenth century Philadelphia merchants built ships and developed a lively trade in flour, cured meat, and barrel staves with the West Indies.

When Penn and his surveyor general first laid out the city, they planned large building lots to avoid the fire and plagues that ravaged crowded 17th century cities like London and to make Philadelphia an attractive real estate venture.

Penn also intended that most houses in the city would have their own gardens and orchards, a novel concept in urban development. Penn’s street plan, which was based on a rectangular grid pattern, was also an innovation in colonial America.

Pennsylvania's Quaker-dominated government emphasized peace and refused to equip a militia.

Like other colonial seaport towns, however, Philadelphia did feel the effects of Britain's effort to reassert economic control over her American possessions at the end of the French and Indian War (1754-1763). Colonial rebellion followed, and Philadelphia hosted the First Continental Congress at the city's Carpenters’ Hall.

The Second Continental Congress in 1775 met at Independence Hall and elected George Washington general and commander in chief of the Continental Army. A year later the Declaration of Independence, drafted and adopted in Philadelphia, triggered the American Revolution (1775-1783).

The Revolutionary War period proved tumultuous for the city of Philadelphia. A number of prosperous Philadelphia merchant families sided with Britain’s King George II during the war and became known as Tories.

( William Howe )

When British General William Howe seized the city in 1777, the delegates to the Continental Congress were forced to flee Philadelphia.

During the occupation of the city, Tories entertained British troops with dinners and dances, while Washington's army encamped in freezing huts with scant provisions northwest of the city at Valley Forge.

When the British left the city, some Tories also departed. Many of those who stayed faced harassment and physical violence, and a few were even tried for treason.

Once America had achieved victory at Yorktown, Virginia, in 1781, and wartime hostilities subsided, the city slowly began to regain its political and commercial stability.

The new nation was firmly established after the British signed the Treaty of Paris in September 1783.

Philadelphia continued to be an important political center as America struggled to build a strong governmental foundation.

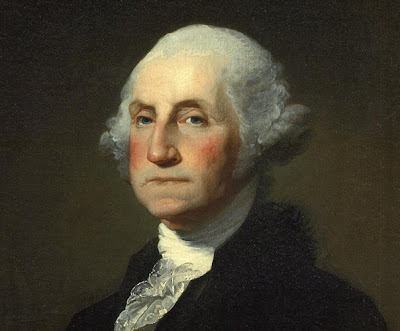

The Articles of Confederation were developed in Philadelphia, and when they proved too loose a binding, Congress reassembled in Philadelphia in 1787 to draft the Constitution of the United States.  ( George Washington )

( George Washington )

In 1790, a year after President George Washington’s inauguration, Philadelphia became the capital of the United States. It remained the capital until the federal government moved to the newly constructed city of Washington, D.C., in 1800.

The last decades of the 18th century also shaped Philadelphia politically and socially. Shipping ventures ranging from China to the Mediterranean Sea enriched many of the city's young merchants.

New immigrants arrived, including many fleeing from the Haitian slave revolt in 1791. The city's population swelled from just under 24,000 to nearly 70,000 between 1765 and 1800.

In fact, by 1800 Philadelphia had become the nation’s largest urban center. Philadelphia’s most influential citizens lived in the area around the State House near the center of the city.

The poor crowded the courts and alleys hidden behind the brick houses of the wealthy. When a devastating yellow fever epidemic swept the city in 1793, killing thousands, these alley dwellers suffered the most.

(1) GROWTH OF INDUSTRY

(2) LOCAL POLITICS

(3) TODAY'S PHILADELPHIA

0 comments:

Post a Comment